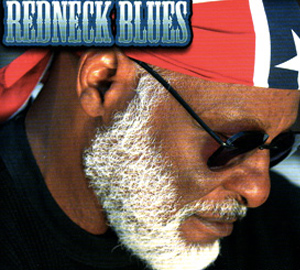

For the past three decades, the blues progressively lost their true symbolical meaning. As the white Gods of showbusiness promptly hi-jacked the blues, the black cry inherent in them gave way to screaming guitars, and festival stages pushed rural juke joints and ghetto taverns into the background.

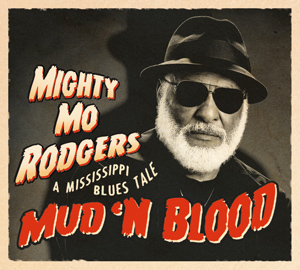

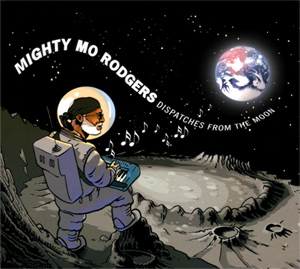

At the turn of the new millenium emerged a mighty prophet who made up for the genre’s dwindling spirituality: Mo Rodgers. Strangely enough, this improbable Savior didn’t surface in Chicago, Holy Land of the blues, but in Los Angeles, modern Babylon torn between Hollywood’s insolent affluence and South Central’s Third World poverty.

Thanks to a revolutionary album entitled Blues Is My Wailin’ Wall, Mo recounted the whole history of the blues, from the slave trade of yesteryears to the current bluesploitation days. Even though he wasn’t the only singer on the contemporary scene with a social or political vision of the blues — one thinks of Chris Thomas King or Otis Taylor —, Mo incorporated into his art, better than his peers, the elements that distinguish the blues from other forms of music : humor, rage, emotion, and a deeply poetic perception of the world, radiantly conveyed by the images he created and the sounds he wrought.